Simply put, a Domain Name System, or DNS as it is shortly referred to, is a set of data lookups which help translate URLs/hostnames into IP addresses. It is often referred to as the phone book for the Internet because it helps the user’s operating system take the URL they input and translate it into an IP address, which then helps the browser locate the resources against it.

Without a DNS, and search engines such as Google, navigating through the internet wouldn’t be as nice and easy as it is. We’d have to track the IP addresses for all of the websites we want to visit and enter each one individually when we want to check them out.

If you still aren’t clear on the concept, let me explain it in detail.

How does DNS work?

The job of a DNS is rather simple. Each web address or URL that is entered into the browser (such as Edge, Chrome or Safari) is then sent to a DNS server, which knows how to map it to its unique IP address.

An IP address is what these devices used to identify each other since they are unable to communicate using names like www.google.com or www.facebook.com. With a DNS, we simply get to enter these simple website names and in the background the DNS does all the heavy lifting for us, instantly returning with the appropriate IP address needed to access the contents of the website.

Again, domain names like www.amazon.com, www.linuxways.com, and www.vitux.com are only used for convenience because it is much easier to remember them instead of the IP addresses.

Computer equipment known as root servers are tasked with storing the IP addresses against each URL. When a user requests a website, the root server is the first step in the name resolution process, and then passes on the information to the next step. Then the domain name is forwarded to the DNR (Domain Name Resolver) which is located with the Internet Service Provider, to determine the related IP address. Once that is done, the resulting information is sent back to your browser and it displays the contents of the website.

DNS cache

Operating systems like Ubuntu and Windows will store IP addresses along with other information about URLs locally on your computer so that they can be accessed faster than having to communicate with the DNS server each time. When your computer gets used to looking up the same hostname multiple times, the returned information is then stored in local storage on your computer.

How does it work

Before your browser sends a request to the outside network, your computer takes a look at each of the lookup requests and checks for it in the DNS cache database. The database contains a list of all the websites you have recently accessed and the IP addresses the DNS calculated for them when they were requested the first time.

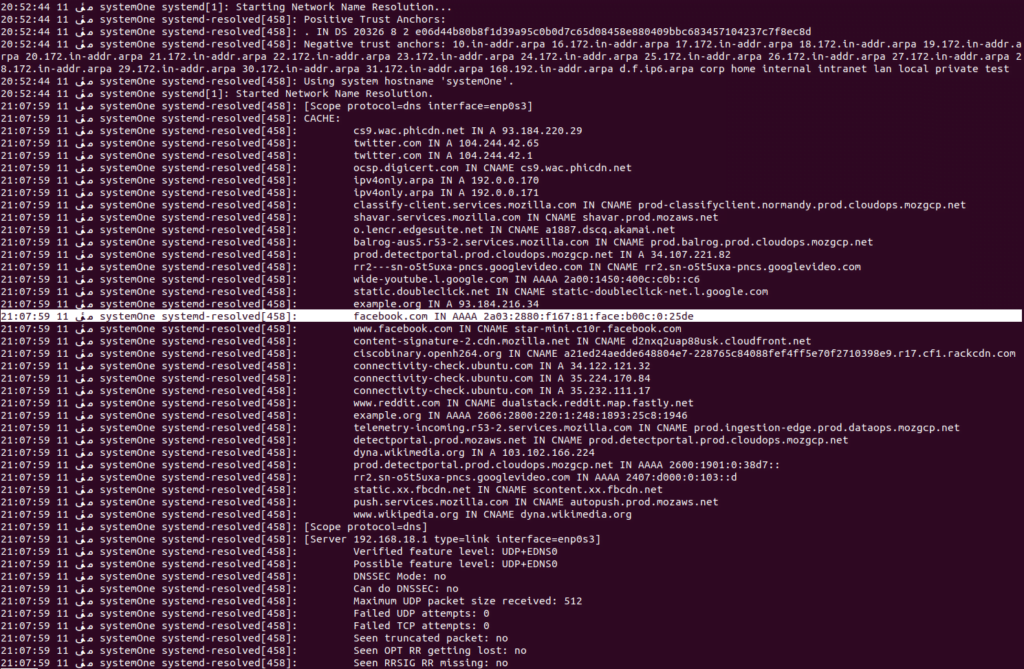

The contents of the DNS Cache on Ubuntu look like this:

If you check your DNS cache on Windows, the contents are much more neatly organized

The DNS Cache stores the IP address along with the requested URL and many other attributes depending on the OS.

How to flush it?

While keeping a track of the DNS information can be helpful, it can sometimes get outdated or corrupted. Generally, your operating system itself removes this data after certain periods, but if you start facing issues accessing certain websites you could try deleting this data or flush your DNS cache to make room for updated DNS records.

Given that it is responsible for directing the browser to certain IP addresses using just the hostname, at times a DNS storage is a prime target for malicious actors. Hackers can infiltrate your local DNS cache and redirect you to a trap and exploit you more and steal your information. DNS poisoning and spoofing are types of attacks, where hackers attack the cache of the DNS resolver to redirect users to malicious websites, regardless of what IP address is truly mapped to your intended URL.

If you want to know how to flush your DNS cache in Ubuntu, you can get step-by-step instructions in our other post titled “How to Flush DNS Cache on Ubuntu 20.04”.

If that doesn’t do the trick for you, you can also try making removing permissions from your host files and making them “read-only”. In Ubuntu, it is located within the “/etc/hosts” directory.

Conclusion

Though you can directly input the IP address for a website into your browser, remembering a URL like google.com is far easier. Doing it, either way will accomplish your objective, it’s because you’re still accessing the same server. That said, if your device is facing an issue contacting a DNS server, you can work around the issue by directly entering the IP address into your browser.

I hope you were able to follow through with the article and understand exactly what’s a DNS and how it works. If you still have any queries or concerns after reading through our DNS posts, feel free to drop a comment below, and let’s chat about it.

Karim Buzdar holds a degree in telecommunication engineering and holds several sysadmin certifications including CCNA RS, SCP, and ACE. As an IT engineer and technical author, he writes for various websites.

Discover more from Ubuntu-Server.com

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.